Original article in Townhall Magazine (pdf)

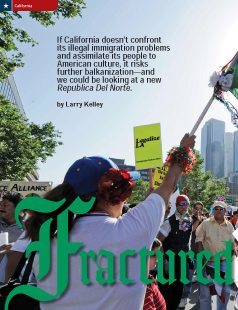

If California doesn’t confront its illegal immigration problems and assimilate its people to American culture, it risks further balkanization—and we could be looking at a new Republica Del Norte.

By A.D. 475, Bishop of Clermont Sidonius Apollinaris had led a five-year heroic resistance against the Visigoths. He recorded his bitterness at Rome’s decision to call a truce and allow the enemy Germans sanctuary in his city: “We have been enslaved, as the price of other peoples’ security.” The imperial government in Rome brokered the Clermont truce based on assurances from the Goths that they would cease offensive operations against the last remaining tax-paying Roman citadels in Gaul—Arles and Marseille. During the following year, both cities fell to the Goths, while the German tribal chieftain, Odoacer, eliminated the last vestige of the Roman Empire in the West and deposed the 13-year-old boy emperor, Romulus Augustulus.

During its ascent and hegemony over the Mediterranean world, Rome displayed genius at being able to rapidly “Romanize” its newly acquired regions and citizens. Yet as the fifth-century progressed, the Senate and the Roman elite families tried to purchase security from the German invaders who were now pouring into the empire unopposed, offering them amnesty and sanctuary, allowing them entry into the empire under their own banners and giving them land in exchange for their commitment to fight the next wave of invaders. In so doing, Rome’s dominion over Western Europe and North Africa vanished.

Los Angeles is the second largest city in the nation with 4 million people. Los Angeles County contains 9.7 million people, of which 47 percent (4.6 million) are Hispanic and a staggering 50 percent are fi rst generation immigrants and their children, a figure that shows how quickly the Latino population in the region is growing. Yet this “redemografi cation” of the region will speed up even more rapidly if the Obama administration goes through with its pledge to grant amnesty to illegal aliens, providing them with a nearly instant path to citizenship and voting rights. This new amnesty will surely trigger a new massive chain migration, allowing millions more newly minted citizens to legally bring into the United States tens of millions of their extended family members—largely poor and uneducated—from Mexico and Central America. Statewide, California’s population of 38 million is now 36 percent Hispanic. Southern California, like the fifth-century Roman provinces, will soon host a foreign-born majority.

Lack of Assimilation

In 2003, classics professor, historian, syndicated columnist and fifth-generation California farmer Victor Davis Hanson wrote Mexifornia: A State of Becoming. Hanson, who says he was reluctant to write the book because he knew the mainstream multiculturalist media would label him a xenophobe and racist, has a farm located 125 miles north of downtown L.A. in the vast San Joaquin Valley, where, for three generations, Latinos have supplied most of the back-breaking manual labor in its fields and orchards. Hanson, whose Swedish great, great, grandparents homesteaded his family’s farm in the 1880s, has seen first hand the impact that the huge Mexican migration—legal and illegal—has had upon California.

Hanson’s book unflinchingly describes the emergence and rapid spread of a completely new hybrid culture—Mexifornia—where millions speak Spanish exclusively and where the civic responsibilities associated with Jeffersonian democracy are completely alien. Thanks to fearless writers such as Hanson and the Manhattan Institute’s Heather MacDonald and the hard work of think tanks such as the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), a detailed picture of the new Mexifornia emerges. It is a place where crime and gang activity are rising to alarming levels and where both are closely tied to illegal immigration from Mexico and Central America. In L.A. County alone, 997,000 residents (8 percent) are illegal aliens and 95 percent of all outstanding warrants for homicide are for illegals.

Investigative reporter Heather MacDonald has found that while most first-generation Hispanic illegals in Southern California work hard at their menial jobs and have tried to stay out of sight, it is their children who are joining gangs in droves, opting for a life of crime—glamorized by the media—over the dreary drudgery of their parents and over the dismal life imposed by a supposedly racist America.

The Center for Immigration Studies’ Steven Camorata points out that this enormous migration across our southern border is far different from any that America has previously experienced. Unlike the Europeans and Asians who came here in the early 1900s and who left their homes, never to return, Mexican immigrants have modern transportation and communication that can and do keep them connected to their homeland. These immigrants living in L.A. can be back in their country in a couple of hours. Today’s mass migration is different because much of the American media, academicians in college Hispanic Studies departments all across the country, elites in Latino racial pressure groups such as the National Council of La Raza, and left-wing political opportunists have all taught Latino newcomers for a half century that the U.S. is a racist country: Because of their brown skin, they are an aggrieved, oppressed minority deserving reparations. It is unlike the experience of our forbearers who arrived as Italians, Poles or Irishmen but, outside their tiny enclaves, found themselves enveloped in a sea of Americans. Today, as Camorata puts it, “They are the sea.” Their numbers are so vast that, in ever-expanding portions of Southern California, Hispanic immigrants overwhelm the American culture and are replacing it with something unforeseen and alien—neither Mexican nor American.

In evaluating this Hispanic mass migration, Dan Stein of the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR) adds two additional distinctions, “This is the first time we’ve admitted a very large group of people with a prior territorial claim. Once you allow a majority of people to populate a region who are not loyal to the national enterprise, eventually you lose sovereignty over that area.” While Hispanic racialist pressure groups such as La Raza, League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán), all operating inside the United States, have each developed a folk-lore that wistfully advocates for the repatriation of Aztlán, (the northern region of Mexico that was “stolen” by “Yanqui invaders”), a Zogby poll revealed that 58 percent of Mexican citizens also believe that the territory of the American Southwest rightfully belongs to Mexico.

In attempting to assess the broad level of fealty toward the U.S. among Hispanic Americans living in Southern California, a partial answer can be found in Jack Cashill’s 2007 book, What’s the Matter With California? In 2006, after Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner’s, R-Wis., Border Security Bill (HR 4437) to halt illegal immigration and protect the country from terrorists coming across our southern border passed the U.S. House, 500,000 Hispanics marched in the streets of L.A. As Cashill writes, the LAPD was expecting about 20,000 marchers, but they obviously weren’t monitoring Spanish-language radio—there are 17 stations in L.A. alone. And predictably, the Los Angeles Times did its best to shield its readers from the fact that above the enormous tide of marchers flew vast numbers of Mexican flags. While the Times might have controlled the message 10 years ago, thanks to the Internet, the Times’ attempt to obfuscate this fact made the paper look foolish.

At the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum in February 1998, 90,000 local fans showed up to watch the top Mexican soccer team play the United States. Cashill writes of the event: “The pro-Mexico fans blew horns and booed riotously enough to drown out the National Anthem. They held American flags upside down. They punched and spat on the seeming handful of U.S. fans in the in the crowd. They threw beer and trash at the U.S. players. The garbage covered the U.S. team like an ugly blanket. … Said U.S. coach, Steve Sampson, ‘This was the most painful experience I have ever had in this profession.’”

The LAPD Gang Detail

In order to immerse myself in this new hybrid Hispanic culture of Southern California, I was able to make arrangements for a “ride along” with the LAPD officers who work the Gang Enforcement Detail.

A few miles from downtown Los Angeles, near the University of Southern California campus, I arrived at the LAPD Southwest Division headquarters at my appointed time of 4:30 p.m. I was to ride along with members of the Gang Detail that works the night shift when the gangs are most active. I was escorted upstairs to a meeting room where the Gang Detail convened each afternoon before heading out on their respective patrols. The group of 10 20-something officers and two somewhat older sergeant supervisors were randomly composed of Hispanic, black, and white men and one white woman.

When I was taken into their meeting, I had the uneasy feeling of interrupting a family at dinner. After police Lt. Davenport’s introduction, their conversations stopped and all eyes fell on me. From my satchel I produced a copy of Townhall magazine and, with extreme brevity, let them know that this is a very “law-enforcementfriendly publication.” They resumed their planning session for few more minutes until police Sgt. Gene Coleman approached and informed me that I would be riding with him.

Coleman is a buff, 230-pound African-American officer who boasts a visage that likely has dissuaded many a gang-banger from resisting arrest, yet I found him to be soft-spoken, genial, informative and professional. He had grown up in South Central near the Southwest Police Headquarters, had served in the Marine Corps and was a 24-year veteran of the division. As we drove through the various neighborhoods and commercial districts, he let me know which gang was in control of the area, the Harpies, Street Villains, Easy Riders, Drifters, 18th Street. I asked him about MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha), a notoriously ruthless and violent Hispanic gang with a strong contingent of illegals from El Salvador that is very active in South Central and growing exponentially in 17 states across the country.

Coleman said that no one in the division predicted the rise of MS 13, mostly because the gang was so uncharacteristically organized, professional and disciplined. He drove us to a commercial district with prosperous looking stores, hotels and office buildings, to an intersection a mile from the center of downtown L.A. As he pointed to a row of second-story windows, he said, “MS called a meeting with a rival black gang called the Playboys. As

Coleman explained that MS-13’s military-style attack decapitated and drove out the rival black gang and allowed MS to run a chunk of L.A. turf near the city center. “I’m sure some of those guys were either from the El Salvadoran military, or maybe even our own,” he said.

And the U.S. government knows how militaristic these gangs are. In her Jan. 26 Wall Street Journal article, “Drug Gangs Have Mexico on the Ropes,” Mary Anastasia O’Grady wrote that the U.S. government’s newly produced “National Drug Threat Assessment for 2009,” written by retired Army Gen. Barry McCaffrey (former U.S. drug czar), exposes the startling fact that Mexican drug-trafficking organizations now “control most of the U.S. drug market, with distribution capabilities in 230 cities.” Her article goes on to report that inside Mexico the government is in jeopardy of falling to insurrectionist drug-cartel fighters who can “outgun Mexican law enforcement authorities and who employ sea-going submersibles, helicopters, modern aviation, automatic weapons, RPG’s, anti-tank 66 mm rockets, mines, heavy machine guns, [and] 50-cal sniper rifles.” Her piece makes clear that, among the vast numbers of violent Hispanic gang members inside the U.S., there is now, ominously, a cross-border coordination with the militarized Mexican drug cartels.

Later that night, I traveled with Sgt. Jessie Garcia, the other Southwest Gang Enforcement Detail supervisor, who explained to me that L.A. Chief of Police William Bratton had provided the department, which is composed of 365 square miles and 20 divisions (each with its own Gang Detail), with a potent weapon: the ability to seek and obtain an injunction against any gang operating in their jurisdictions. Getting an injunction involves convincing a local court of a gang’s criminal activities. Virtually all the identified gangs in the Southwest Division have injunctions imposed upon them, meaning that known members can be taken in and questioned for congregating in groups of two or more or for various activities such as putting up gang graffiti, even on one’s own home.

Shortly, we heard over the radio that some new gang graffti had been spotted nearby and that a couple of officers were already there. When we arrived at the scene, a side street in a residential area, we met Officer Guillermo Espinosa, who illuminated me as to why decoding graffi ti is serious police work. “This was put up by a new offshoot of the Harpies. [See photo on Page 56] In the beginning of this string you have the ‘DE’ that stands for ‘Dead Enders’ and the ‘X3’ shows any other gang member that this group is under the protection of the Mexican Mafia.”

Espinosa explained that the group calls itself the “Dead Enders” as a reference to their long-ago peaceful beginnings when they congregated in neighborhood cul-de-sacs, fi xed up old cars and played soccer. The “X3” refers the 13th letter in the alphabet, M, which in turn refers to the Mexican Mafia, now a powerful overlord of Southern California Latino gangs, an organization that traces its beginnings to a prison in Tracy, Calif., during the 1950s. Its charter claims allegiance to the Aztec civilization. And it has gained a stature similar to the elders of a distant tribal past, a gangland overlord status enforced by ruthless, murderous force. It arbitrates disputes, issues execution orders and governs the criminal enterprises of much the Southern California Hispanic underworld. It would seem that, as Dan Stein envisions, under the right circumstances, the Mexican Mafia could also provide a catalyst for a massive insurrection, issuing a call to arms to join in a Latino populist revolt aimed at challenging U.S. jurisdiction and recapturing the stolen Aztec homeland.

Wandering South Central by Day

On my second day of immersion in South Central, I drove and wandered around the neighborhoods and back streets of South Central Los Angeles and neighboring Huntington Park and Maywood in an attempt to uncover the defining elements of the new Spanish-speaking America. Having seen poverty in Mexico and Central America during my vagabond years, what I observed in L.A. was very different in numerous respects. Off the main commercial thoroughfares, in residential back streets, one sees endless rows of small, very tightly spaced homes, many with bars on the windows and made of cheap, aging construction, but unlike much of the impoverished Third World, there are very few homes littered outside with refuse and junk. Moreover, the streets are clean. In short, it’s clear that, even in the most gang-dominated “hoods,” there is among the inhabitantsa pride of ownership.

Also, unlike the Third World, in Mexifornia, people are not going hungry. It was obvious that a large percentage of the young people, especially the males, were not only not hungry but overweight.

One of the most telling traits of Mexifornia is the language. In Huntington Park, I saw the largest concentration of store-front signage written in Spanish. There is even an all Spanish-speaking shopping mall, Mercado del Pueblo (the Town Market). It’s a collection of businesses housed in what is a converted industrial warehouse with mechanical chain-operated roll up doors. I stopped in a restaurant, El Ranchito, where the patrons were speaking Spanish and watching a Mexican soccer team play on a Spanish-language television. After ordering a quesadilla and a Coke at the counter, I sat down at one of the booths. When the waitress arrived with my meal, I made an attempt in my rusty Spanish to strike up a conversation.

“Cómo se llama?” (What’s your name?)

“Estella,” she said with a smile that let me know that she was amused to have a gringo like me come in, order a meal, and speak to her in Spanish.

“Vive aquí en Huntington Park?” (Do you live here in Huntington Park?)

“Sí.” (Yes.)

“Estella, cuantos años vive aqu?” (How many years have you lived here?)

“Once.” (Eleven)

“Habla inglés?” (Do you speak English?)

“No.”

The Best Ride Ever

At 4:30 p.m., I arrived at the Southwest station for my second night “ride along.” I was told that most of the Gang Detail, including the supervisors, were out at a crime scene where there had been a double homicide. So I was escorted to their meeting room where I looked at the walls full of mug shots of tattooed gang members for a while. After they all returned, Sgt. Garcia approached me with two of the youngest officers of the unit following him. “You’ll be riding with these guys tonight,” the sergeant said. He then turned to them and said emphatically, “Don’t get involved in anything.” From this I took him to mean: With a civilian along, especially a reporter, don’t get into anything that might get dangerous.

We promptly left the building and got into the squad car that was parked in a back parking lot. With Officer D at the wheel and Officer B riding shotgun, I sat in the back seat. (The officers’ full names have been omitted for reasons that will shortly be apparent.) Immediately after we exchanged introductions and pulled up to the electrified gate, Officers B and D became riveted to radio communications, audible inside the cab. A couple of plainclothes officers had spotted and were tailing a guy who was wanted for a murder he allegedly committed inside the Southwest jurisdiction.

A couple of seconds after the electric gate had opened to allow us out onto the road, Officer D floored it, sending the squad car roaring down the four-lane Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard at rush hour. With the dispatcher updating the location of the suspect’s white GMC Yukon over our radio, Officer D was coolly transformed into equal parts urban warrior and NASCAR driver. As we sped toward major intersections where cars were stopped in front of us at a red light, Officer D swerved left into the empty on-coming lanes, speeding toward the intersection where he fi red up his siren and lights, thus freezing the cars that were coming toward us on our right and left. At high-speed, tires squealing, he wove through the stopped cars at the intersection and roared off down the empty right side lanes. At other moments, Officer B would spot an empty side street and say tersely, “On yer left, take that one.” Next, we’d swerve into a side street, roaring down it with sirens blaring, on a shortcut that allowed us to avoid a stoplight.

When we made it to the freeway, Officer D opened it up, taking us down the inside shoulder of the median. When we pulled up near the white Yukon, we were in the city of Hawthorn, 20 miles from the Southwest Division Headquarters, having made the trip in about 15 minutes at rush hour. From the calm demeanor of Officers D and B, this was just another day at the office.

We were the second squad car to join in the pursuit, causing the suspect to realize he had drawn the heat. Suddenly, he stopped his car in the middle of the street, leaving a sack of drugs and his girlfriend in his truck, and ran into a house that we later found out was his parents’ home. Officers D and B parked at one corner and, with the help of other arriving squad cars and a whole lot of crime-scene tape, set up a perimeter, closing the whole residential city block to cars and foot traffic. Soon a police helicopter was loudly circling at low altitude overhead with a huge spot bathing the house in bright light. Next, the canine units arrived and a crowd of spectators and temporarily homeless residents gathered. Officers D and B politely explained to those who were wishing to return to their homes that, for their safety, they needed to remain behind the tape until the suspect was apprehended.

During the two-hour standoff, Officers D and B told me that the guy they were pursuing had been at large for about a year and was a member of 18th Street, a particularly violent Hispanic gang that had gone to war and driven out of South Central a black gang called the “Gear Street Crips.” “These guys got a hold of automatic weapons and killed a whole lot of Crips,” Officer D said.

With the dogs poised to enter the house, one of the units was able to get phone contact inside the house and convince everyone in it to surrender. First a grandmother, then father, brother, sister and lastly the “perp” came out the front door with hands raised. Each was cuffed, searched and led to a squad car outside the perimeter.

On our way back to Southwest Headquarters, we chatted about the nature of Hispanic gangs, and both officers agreed that what is different about them now, especially in contrast to the black gangs, is that they are much more organized than they used to be—more structured, disciplined and lethal than ever before. “Murder is the way they gain respect. Sometimes they even kill their own gang members because it makes them feared and respected,” said Officer B.

“We talk to these gangsters, and we can joke with them,” Officer D added. “But we know if they could kill us, they’d do it in a second.”

What Next for SoCal?

By the mid-fifth century, the Roman Empire was losing jurisdiction over its provinces. Small farmers and merchants abandoned their lands and businesses in order to escape the Roman army whose primary function was reduced to imposing crushing taxation upon those citizens still loyal to Rome. The provincials fled to the breakaway proto feudal estates of powerful generals who maintained their own armies, law codes and even prisons.

Sgt. Coleman told me that when he grew up in South Central, if a single homeless person was seen wandering the streets, police were called. Now, as the city of Los Angeles rapidly becomes majority Hispanic, there are 57 gangs operating in the city limits, 40 of which are Latino, with new mutations forming new gangs at an ever-increasing rate. What will greater Southern California become when there are 100 gangs in L.A.?

Is it possible that a new Che Guevarastyled revolutionary could arise, rallying his Hispanic gang-linked brethren to conduct massive civil disobedience, combined with pockets of sporadic armed insurrection? In Mexico, the drug cartels already control an estimated 200 counties where they have set up new “narco city states” with their own armies and, through extortion, have set up parallel tax systems that replace the government’s ability to levy taxes.

In these vast balkanized, Spanish-speaking areas of the American Southwest, the Mexican drug cartels, the Mexican Mafia and myriad other U.S.-based Hispanic gangs could be mobilized to reject “Gringo” rule in favor of establishing a new Republica del Norte, a breakaway state promoted by a wide coalition of the pro-Aztlan groups. Such a state, nominally aligned with an enfeebled Mexican government, is a nightmare scenario that becomes much more likely if and when the old majority of white European, Asian and African-Americans in larger numbers give up on the region and migrate to safer zones where a more traditional American culture still exists.

As Dan Stein at FAIR points out, at some point, any central government must do a cost-benefit analysis as it determines what to do about a hypothetical breakaway province. In 2002, a study determined that each family of four in California paid $1,200 a year in taxes just to house, educate, medicate and incarcerate the state’s illegal alien population. How much blood and treasure will or could our cash-starved government expend to prevent the secession of a region that is already a net drain on its treasury?

But There’s Hope

As Hanson writes in Mexifornia, “California has always been a risky experiment.” Southern California has been, for a couple of generations, a prime mover of America’s ubiquitous pop culture, which is dispensed by Hollywood, the music industry, video games, television, colloquial language and fashion and which, despite its nihilistic glorification of the hoodlum, nevertheless has a unifying effect on our young. The pop culture is so pervasive that it tends to overpower the mores and customs of both traditional America and Mexico. In this regard, Hanson concludes that, in a strange way, we’re lucky to have pop culture because it buys us some time in our attempt to alter the many destructive trends attendant to this massive migration across our southern border and our failure to educate and assimilate Mexico’s unwanted poor.

There is hope for assimilating Spanish-speaking Southern California, because America is both a place and an idea. It is a place where there is no defined class structure, where racism and ethnic hatred are now mostly fictions peddled by increasingly marginalized race hustlers and where success can be had without any preconditions, despite the fact that our political class imposes an ever more oppressive taxation upon the middle class. America is a place where millions still try to break in and few wish to leave.

Our pop culture can still produce pro-American films such as The Patriot and Saving Private Ryan. Southern California is still an American citadel that produces men and women such as the heroic officers of the Southwest Division’s Gang Detail, defenders of the land of the free and the home of the brave, the bold blue line that exemplifies our core values—one of which is courage under fire. Before any kid growing up in South Central joins a local gang and kills a rival gang banger, he will have encountered many times men and women such as those I met in the LAPD, those who personify the reason for preserving our civil way of life, men and women who are living proof that, unlike Mexico or Cuba, America is still the last best hope for mankind.

NOTE: Published in Townhall Magazine

groupbuy enjoys completely free boost… through a civic action institution. Third party brief article presents you with Ten new stuff around groupbuy that not a soul is talking about.